I will put before you the arc of my career, making an assessment of its major landmarks, themes, formal epiphanies, and most importantly, its vision for the future.

I begin my written narrative from the present-day working backward because I find myself at an odd and interesting juncture, one year after Hurricane Sandy destroyed my studio in Red Hook, Brooklyn. Flotsam and jetsam of past work literally floated to the surface of the waters, and in so doing, gave me the (unasked for!) opportunity to see, before me, like the bottom of an upended pyramid, the foundation of what has driven me for the last thirty years. Community; the deeper meanings of ‘Home’ and ‘Family’; the Human Body and the Social Body; Interrelation; Absence; and, on a formal level, Texture and ‘Touch’. These are the themes I can’t stop investigating and ‘worrying’ like jade beads in my hand. I’ve had a career that’s been international in scope—including more than 140 exhibitions in museums and galleries on three continents, teaching positions in notable academic institutions (from Pratt to SUNY New Paltz), artistic directorship, and I’ve created, literally, thousands of prints, (including a celebratory Anniversary Portfolio of 20 years in 2011). Yet I am driven to ask myself at this juncture: What is Mastery? When will I know I have attained it?

PERFECT STORM

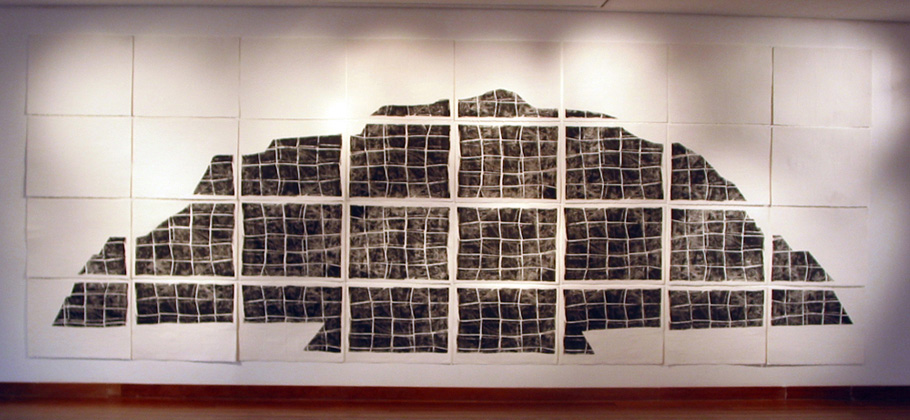

In 2011, one year before Sandy hit (ironically enough) I set about assiduously rubbing (in brayer and black etching ink) every inch of wall space in my 2,000-sqft Red Hook studio in preparation for the exhibition Retroprospective in 2012. Since my studio has been for decades the substrate of most of my work I lifted on paper the bas-relief hand-worked textures created by brick and mortar. The impressions of these walls—Brick-by-brick, were exhibited in the Museo de las Esculturas, Mexico creating a life-size paper replica of my studio for visitors.

One year later, because the motor of my Charles Brand Etching Press, along with numerous other materials, were damaged by saltwater from the flooding, I resorted to making limited-edition photographic prints and lithographs. In the series Before and After, one photo shows the walls with the patina of green moss and salt that accrued even after a crew had come in several times to clean; the other, the pristine white ‘rubbing’;

another bifurcated print shows the flood line made by mud abutting, in a perfect line, the line a local curator had drawn in an exhibition entitled Flood line. In the exhibition, my work from 2010-12 was hung above and below her painted, hand-rendered line, sealing, in effect, a gap between time and space, loss and the future.

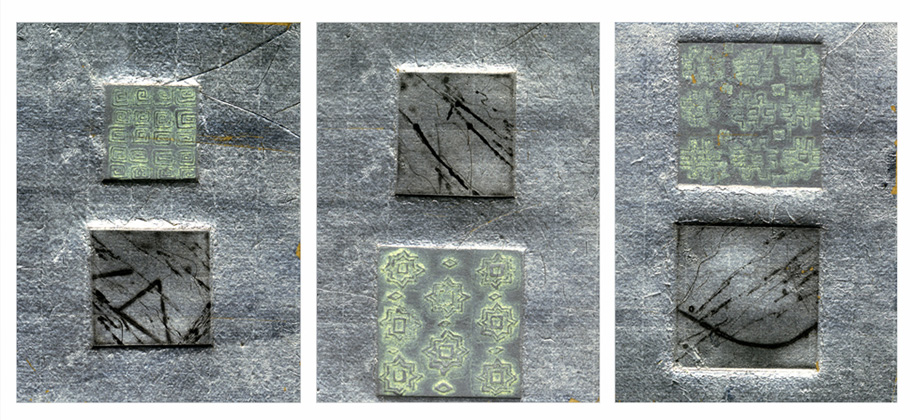

In 2013, Brooklyn Arts Council invited me into a group show For & About: Art & Reactions to Superstorm Sandy, to which I contributed lithographs of satellite images and my interpretation of patterns created by the storm (Anachronic Patterns, 2013). With the studio still unusable, I went back to São Paulo (where I was born), visiting all the women in my family there. I brought a rescued brass plate and had them meet up—generations of women from the age of 17 to 84—and work cutting patterns of felt into endless chain links. They told family stories as they worked–sometimes about those who had passed on, removing the fabric to reveal the chain patterns as they did so. So Deeply Felt was first exhibited in piles of chains of varying dimensions in Etnia VII, Belgium, and Record of Absence were shown hanging in Eu-concreto in São Paulo. For me it was a revelatory lesson: When something is removed, what remains is thrown into stark relief. Sometimes our formal, artistic practice can show us truths about how to live our life.

Still, without the use of my inoperative presses, I worked outside in an encaustic studio on a series of small diptychs incorporating scavenged materials from my Red Hook studio into the mix. Called Mended Structures, they preserve, in wax, old damaged prints and cutout copper plates.

COMMUNITY

During the twenty years prior, I would have to say that my most proud accomplishment is that, even as I created my own work, I continued to provide an environment—Goloborotko’s Studio (Studio)—where others could collectively create their art as well. I will ‘rewind’ the decades here to let this unfold, starting from my school years in Brazil to 9-11 in New York.

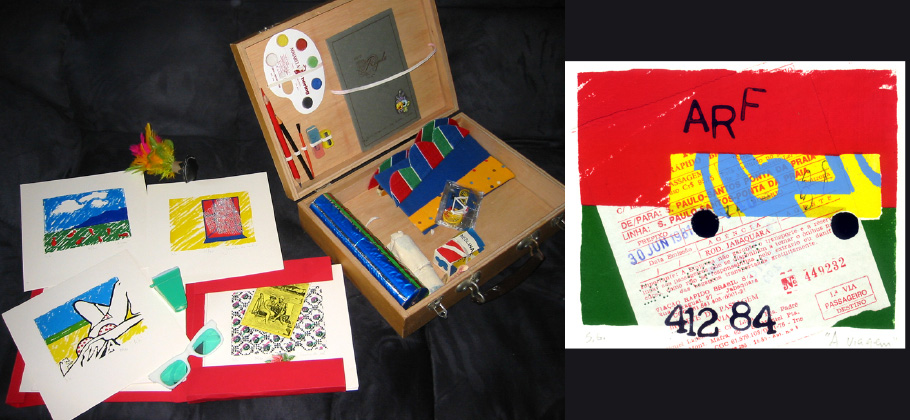

In 1981, I receive a Bachelor’s Degree in Architecture and Urban Planning from the Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo de Santos, Brazil (due to the fact that, during the military dictatorship there, fine arts schools were decommissioned). I come to the US seeking the artistic freedom my home country lacked (though I will later return, and often, to exhibit and collaborate). I earn an MFA from Brooklyn College in 1985. I print for Keith Haring’s Pop Shop and earn a decent living silkscreening, enough to co-edit Crossings, a series of editioned artist’s books and create my own ad-hoc installations. No matter what mediums I will explore from this point forth (sculpture, ceramic, painting, drawing, theater) printmaking will always be my home. I work as an adjunct professor of Printmaking at my alma mater until 1998. I rent my first studio in DUMBO—and this becomes crucial to my community activity, setting its tone.

In 1989, realizing that even in DUMBO artists had no venues to collaborate I opened the doors of my studio and transformed it into a community printshop. Hands and Eyes on Printmaking, received funding from Brooklyn Arts Council from 2001-2012 (except 2007 and 2009) to support a monthly open workshop to artists at various levels of expertise. People with limited exposure to printmaking worked side-by-side with accomplished artists. Until 2011 Goloborotko’ Studio was the only printmaking facility offering open workshops to the general public in Brooklyn.

MASTERING TECHNIQUE, EXPLORING MATERIALS

I begin post-graduate work in Studio Arts at NYU in 1985, working on a series of color viscosity prints—Bestiary—under the tutelage of sculptor and printmaker Krishna Reddy. Inspired by Reddy’s revolutionary printmaking approaches the scope of my work evolved exponentially: I broke through a barrier I had heretofore perceived between 2- and 3-dimensional mediums and was able to make a thematic through line. By 1987, however, structural changes were made to the original Ph.D. program, and I felt I had no choice but to move on.

Inside my studio in the early 1990s, I explore more exotic materials and subject matter. Meanwhile, outside my doors, I feel compelled to reach out to the public in what was becoming a quickly gentrified neighborhood, creating large-scale, site-specific public installations in empty industrial lofts. I learned that to earn the title of “Master Printmaker” your studio doors must always be open. It is the nature of serving the wisdom of this incredible craft.

EXPANSION

My locus shifts to places, causes, and mediums outside my comfort zone/home base. In 1992 I create a site-specific installation Swimming Pool—a 3,000-square-foot waterless pool in the Museum of Contemporary Art in São Paulo. Over two thousand people visited this installation each weekend for four months and submerged themselves into a frozen landscape of cutout swimmers and distorted printed tiles.

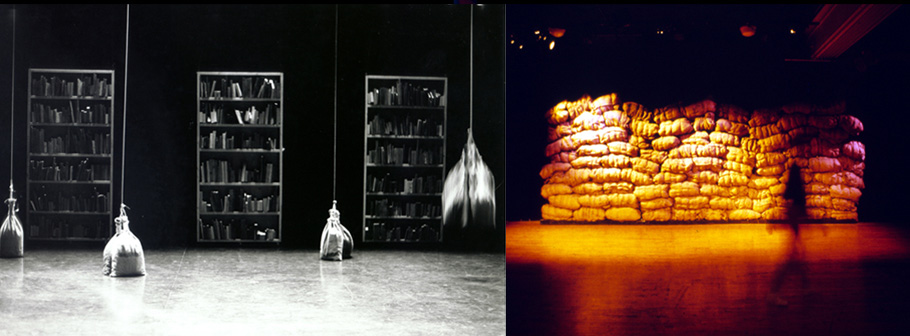

In the mid 90’s I venture into collaborations with off-Broadway performances creating sets for over a dozen productions. These included a set design for a Heiner Müller play directed by Martin Wuttke of the Berliner Ensemble, in New York and for choreographer Bill T. Jones at the Dance Theater Workshop—incorporating, among other things, kinetic elements such as sandbags that responded to the dancers’ movements.

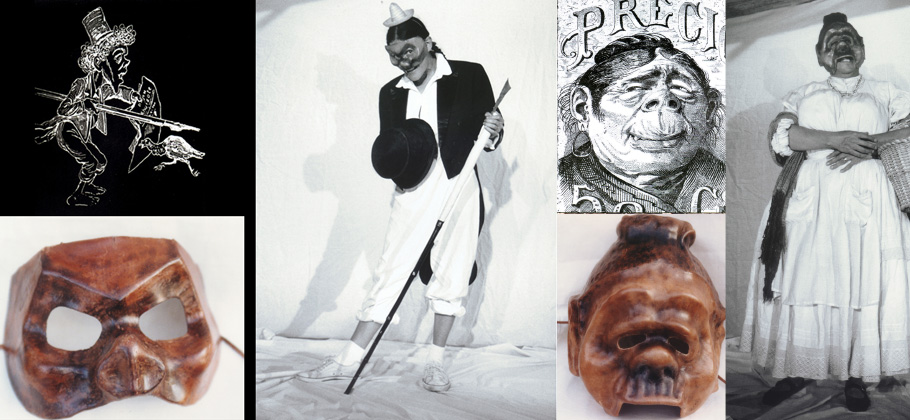

In 1998, Jesusa Rodriguez, a prominent theater director, invites me to collaborate on La Chinga, a street, and theatrical production in Mexico City over the course of nine months. My job was to translate Mexican prints from the late 19th Century into masks, sets, and costumes. I research ancient Mexican civilizations, architecture, codices, and cosmogony as they all permeated and transformed my own work.

Upon my return, I create Cuilcuilco, a large-scale mural print inspired by a late Pre-Classical ceremonial cylindrical pyramid. The subject matter of my lexicon matures and becomes something more universal. I learn how to become a witness to world events and history with my shapes and abstract narratives.

BACK IN THE STUDIO/BACK IN THE BODY

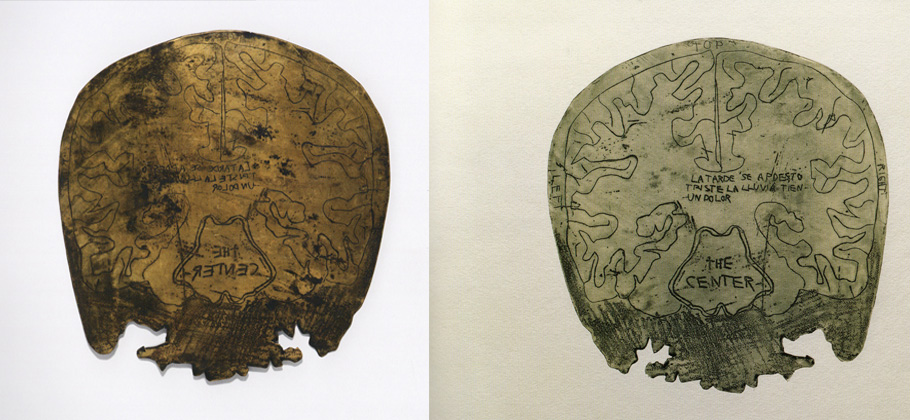

So, in the mid-1990s, my work becomes my way of exploring social themes; that said, during this same period, I don’t shy away from bringing my personal and family life, laying it on the line in this inquiry. I respond to my mother’s passing in 1995 with no small amount of personal stress, including facial paralysis (long since past). The physical body, our failed and faulty design, hearts, hands, and eyes became the new (and later, recurring) images in my prints. A massive wall of recycled offset brass plates depicts sections of my brain, based on my own MRIs. These became self-portraits, maps of my conscious and unconscious mind. I mapped my own existence internally and externally. Sensus Communis, this installation of prints and plates, marked my location and brought me hope that I would not get lost.

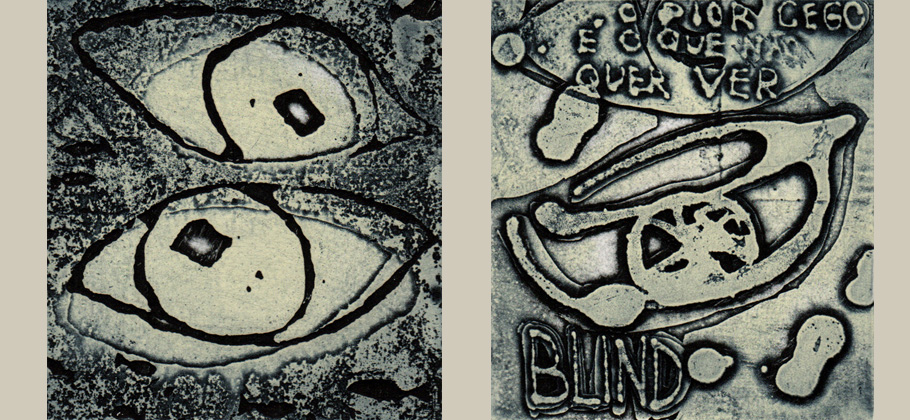

From 1993 to 1995, I let the work I make in the printmaking studio speak for AIDS. I create a series of prints, a chain of fragmentary eyes that narrates the fear that my younger brother, who suffered from the disease, was having of losing his vision and life. My brother (a marine biologist by profession) wrote the prologue to this portfolio of ten prints entitled Eyes That Saw and Became Fish. Later, after he died, the series was purchased by The New York Public Library, Rare Books, and Manuscripts Collection and exhibited there.

THE 2000s: REAL LIFE AND REAL DREAMS

2001, and, like many New York-based artists, I witness the tragedy of 9-11. I begin a theme that will become both formal and personal: What is left when everything is lost? And in its spirit, I create Objectos Alogicos, a series of small clay sculptures. These pieces are Saggar Fired—a process where organic material is fused onto clay in a gas firing. These fossil-like objects describe the way in which a single shape cannot be reduced to the rationality of logic.

The ensuing years are a flurry of activity—and art world recognition and projects. In 2004, the Museu Estação Pinacoteca in São Paulo curates a solo exhibition of my work to inaugurate its new wing for contemporary prints. This exhibition presented ten years’ worth of work rooted strongly in the tactile, traversing boundaries of materials. Steel wool became a printing material and a sculptural element in a number of projects that followed and chain links and words illustrate how we are all interconnected.

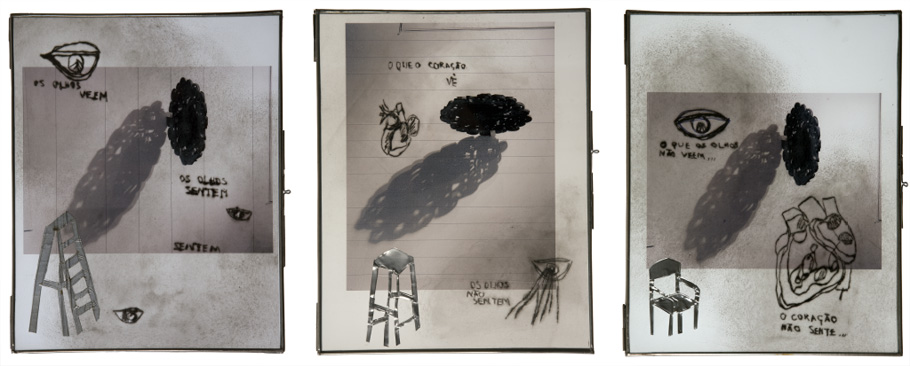

In Witnesses, mundane studio objects (a stool, chair, and ladder), become my muses, represented in prints and ceramics. Interested in the fabric of life I Got You Under My Skin links parts to a whole culminating in nature with a series of silk-moth images both larger than life and small: Silk Is Soft: Life Is Hard.

Transformations come in all forms, often when we aren’t even conscious. So, two years ago, I initiated 1001 Dreams, an ongoing public intervention in which pedestrians find pillowcases, printed by me, that depict the text and scene of a stranger’s dream. (On the back of pillowcases these passersby find a link to a blog site and are asked to submit a dream.) Viewers are welcome to take these soft found objects home, rendering the private public, and the public, private. Making material of what is immaterial this project facilitates collaborations among strangers. To date, this project has been ongoing on the streets and sidewalks, the train stations, and parks of São Paulo, London, and New York City. I will not stop until 1001 Dreams are amassed.

In summation: co-creating with the public has afforded me my current sense of ‘Mastery.’ But it is the mystery, the ‘dreams,’ behind these creations that keep me engaged in a relentless, material Practice. To paraphrase Carl Jung: “Who looks outside, dreams; who looks inside, awakes.”