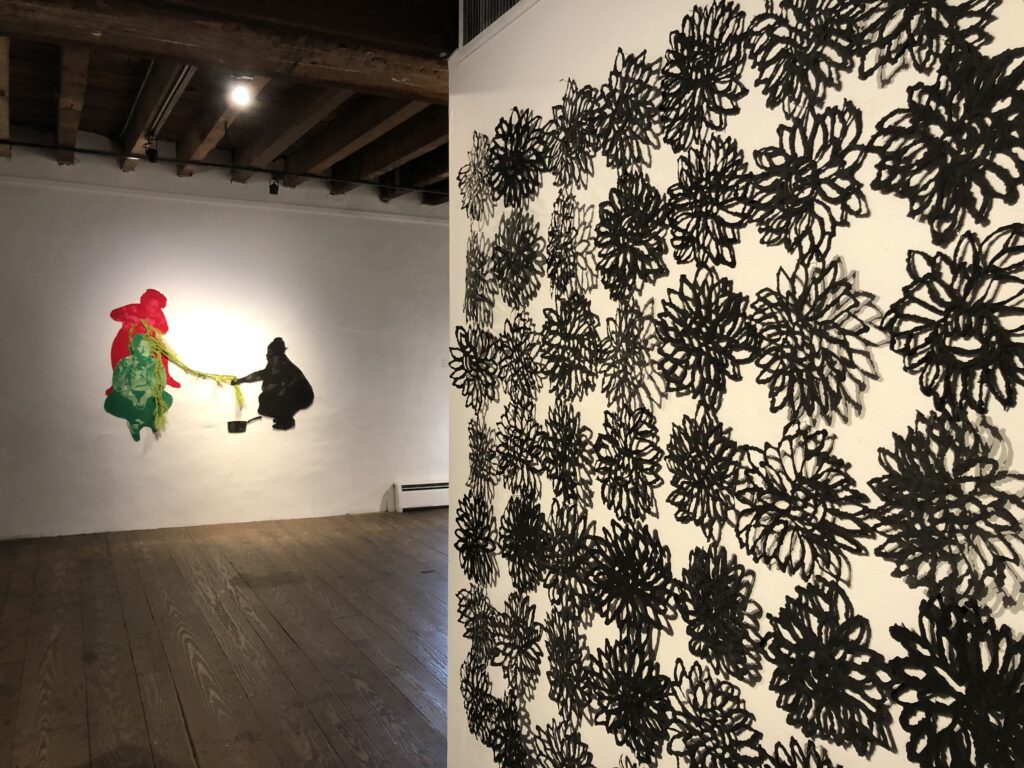

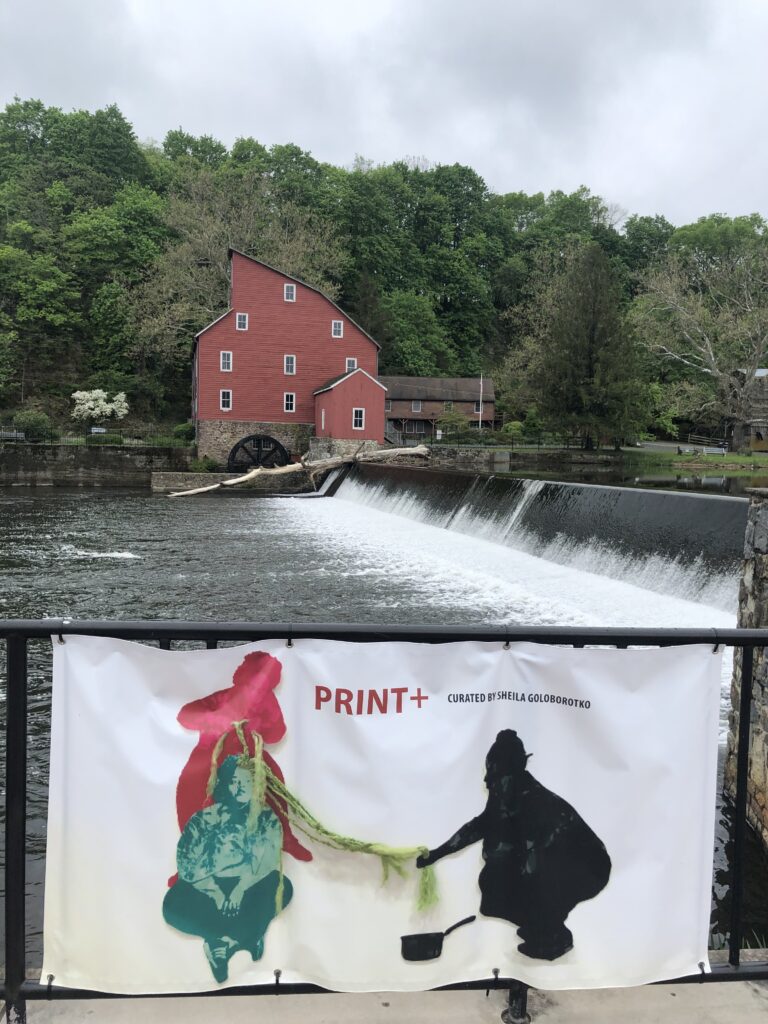

Print +: Sameness and Otherness in Contemporary Printmedia

Hunterdon Art Museum

Clinton, NJ

May 8 – September 5, 2021

The exhibition you are about to see includes such a diverse group of makers and methods that it would take a catalog to tell you all about what this show is. (It’s called “Prints +” for a good reason.)

However, we can quickly tell you what it isn’t:

rigid; exclusive; finite; complacent; frightened by change.

Now let’s explore this garden of makers and methods you are about to walk through. They are gay, activist, straight, male, female, trans, queer, old, young, white, black, indigenous, people of color, and immigrant. They are disabled bodies and bodies in transformation — yet not one artist would want to be defined by such singular terms. Each with their own unique experiences and intersectionalities would much rather we focus on how they see the world and the risks they take to show it to us so honestly.

Eric Avery makes artwork that is centered around infectious diseases. The image he contributes here will literally sprout from the seed before your eyes. Daniel Luetke is an HIV-positive artist. His work, at first glance, may look like a pleasing mosaic of ceramic tiles in repeating color patterns. Look closely, and you will see that he layers those tiles with prints of his own urinalyses and blood tests.

Kat Chudy stamps on the medical gowns that they actually wore for MRIs. Raluca Iancu prints on large fabric that she inhabits and performs; Ann’ Sole Sister’ Johnson transfers letters on glasses that reveal what we can and can’t see; Mildred Beltré Martinez prints an amulet against the evil eye on dish towels while Alison Saar uses handkerchiefs and shop rags to comment on color-diverse skin and socio-economic status.

In the hands of Wendi Ruth Valladares and Imin Yeh, prints become both replicas and reliquaries—in the shape of a flower, salt, frame, a film projector, and cassette tapes; for Melissa Harshman they become floating memorial gardens, and Sangmi Yoo, wove tapestries depicting flora and space. Paper becomes a butterfly catcher for J. Leigh Garcia; Cai Quirk photographs depict rituals of bodily transformations, while for Melanie Yazzie and Hope Mc Math print is storytelling—one reflects her Dreamtime friends and companions while the other registers the daily historical events.

Tatiana Potts’ architectural builds uninhabitable spaces from folded prints; Emily Arthur imprints the history of genocide in organza to wrap an extinct bronze cast bird, while Leslie Dill uses Emily Dickinson’s poetry to wrap an un-gendered body. Miguel A. Aragón and Cassandra Gunkel print portraits of the ones we lost in hope that the memories of nameless victims won’t be erased by history or forgotten.

In Sara Carter’s work, hair is the connector in a private domestic scene and hair is what is left in Althea Murphy-Price. She uses lace tablecloths like a stencil, but instead of ink, her mark-making substance is synthetic human hair. The hair creates a powerful and clearly tangible “print”—but only for a short while. Such a light material must ultimately blow away.

Can an ephemeral image be considered a print? Absolutely. There is a printing element here that allows the substrate (paper, glass, or fabric) to receive the image—and witness what has been created. “Witness” is the essence of what a print does and how it functions from inception to the present day. It will outlive lifetimes; its power will exist after fad and upheaval. A print is something that leaves a mark. We all strive to make a mark during our lifetimes. We leave it to history to do the rest.

Sheila Goloborotko, 2021